At 11am on September 1st, 1859, the English astronomer Richard Carrington stood in his private observatory recording images of the sun.

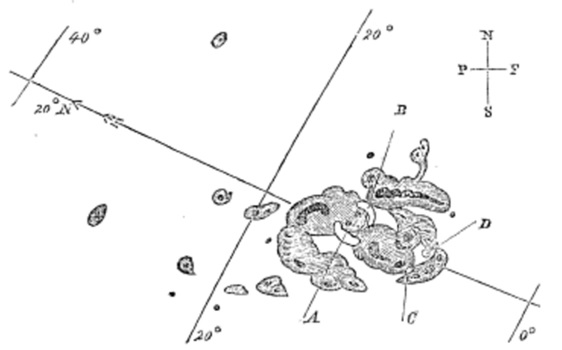

Staring into his telescope, he saw something very strange.

“Two patches of intensely bright light broke out”, he would later write.

“My first impression was that by some chance a ray of light had penetrated a hole in the screen attached to the object-glass, for the brilliancy was fully equal to that of direct sunlight”.

In fact, Carrington was the first witness to a rare event.

A giant solar flare was headed to Earth, sweeping up detritus in a magnetic current that light up the sky in a huge storm.

In this mostly pre-electric age, most people experienced the event as a giant light show.

Skies that night were washed over with red, green and purple auroras so bright you could read by them.

Very few things were damaged during the storm.

When the magnetic force of the flare hit a telegraph operator, it might have delivered a sharp shock.

Papers in telegraph offices caught fire.

At that point it was the largest solar storm ever recorded.

But next year could see an even bigger storm.

And it could play out very differently…

Why suncycle 24 is so dangerous

Over the last few decades, scientists have been able to discern a regular pattern in suns behaviour.

The sun is effectively a giant ball of gas that rotates on a monthly cycle.

It turns faster at its equator than the poles.

The effect is to create a dynamo that makes a magnetic field which throws out magnetic explosions at irregular intervals.

These are visible to us as sunspots.

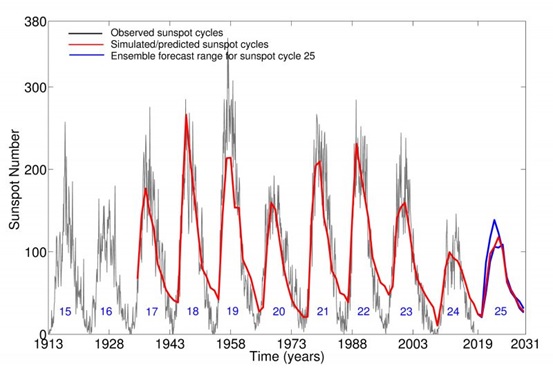

The size and frequency of these spots seem to follow a 22 year cycle in which solar actictiy peaks every 11 years.

After peaking in 2014, the solar cycle is entering its low phase next year.

And it’s expected to be a very low one.

According to Professor Valentina Zharkova of Northumbria University, the sunspot cycles have been increasingly weak over the last century.

The most recent cycle had a maximum that was long overdue and it was also smaller than previous cycles.

And that’s cause for concern.

Because when we have seen this formation in the past, there have been some dire consequences.

What might a massive solar storm look like in 2019?

1. A Flash of Lights

Well unlike 1859, we’d have a bit more warning this time.

Today we have i nstruments all over the world and in Space monitoring the sun from one second to the next.

But even at the speed of light, a massive solar flare flash of radiation would leave us with just a few minutes to prepare for a giant incoming wave of particles.

That’s when the trouble begins..

2. Rolling Blackouts

The storms would cause havoc with our global tech systems.

The magnetic charge would course through every electrical system, causing a giant surge that might knock out everything connected to it.

A “Carrington Event” today would lead to the simulatanous loss of GPS, mobile reception and much of the power grid.

I n 1989, a flare struck Quebec and Canada leaving six million people without power.

In 2003, flares forced the crew of the international space station to take cover.

3. Blind Landings

Meanwhile the global aircraft fleet would have to coordinate mass grounding without satellite guidance.

The Met office is concerned that the UK is especially vulnerable to attack due to “our high reliance on satellite technology”.

Damage to computers, data transmission cables and power lines could cost the country up to £16bn, it claims.

(Have a read of my recent Monkey Darts on the Satellite Boom to see how you can profit.)

4. $2 trillion in damage as all our systems collapse

“Humans in space would be in peril, too”, say NASA.

“Spacewalking astronauts might have only minutes after the first flash of light to find shelter from massive energetic particles.

Satellites could burn up, destroying communications systems and causing burning space junk to fall into our atmosphere.

Overall, the best available estimates suggest between $1 trillion and $2 trillion of damage in the first year.

But that isn’t the worst case scenario.

5. A Mini Ice-Age

Prof Valentina Zharkova gave a presentation at the Global Warming Policy Foundation last month.

It was a disturbing talk.

You can watch it here.

Zharkova has modelled solar sunpot and magnetic activity for decades.

Her models “run at 93% accuracy” and suggest that we could be headed for what’s called a “Super Grand Solar Minimum” in 2020.

When this event happened 350 years ago, it lead to a massive dip in temperatures for 40-60 years.

The last time we had a little ice age only two magnetic fields of the sun went out of phase.

This time, all four magnetic fields are going out of phase.

Zharkova is predicting a mini-ice age that could last for a century.

The current sunspot cycle, dubbed solar cycle 24, is just ending – as it plays out we could see a series of strange weather events in 2019 that put even more pressure on stressed farmers.

We’ll do our best to warn about the incoming storm here.

Good luck everyone.